Chapter 1 Preliminaries

“In the beginning, the universe was created. This has made a lot of people very angry and been widely regarded as a bad move.”

— Douglas Adams

“The history of life thus consists of long periods of boredom interrupted occasionally by panic.”

— Elizabeth Kolbert, The Sixth Extinction

1.1 Course outline

Day 1 – In the Beginning

- Presentation: Preliminaries

- Exercise: It which shall not be named

- – break –

- Demonstration: The New Age

- Interactive Session: Introduction to R and RStudio

- – lunch –

- Interactive Session: An R workflow

- – break –

- Interactive Session: An R workflow

- – end –

Day 2 – Show and tell

- Interactive Session: The basics of

ggplot2 - – break –

- Interactive Session: Faceting figures in

ggplot2 - – lunch –

- Interactive Session: Brewing colours in

ggplot2 - – break –

- Assignment: DIY figures

- – end –

Day 3 – Going deeper

- Interactive Session: Mapping with

ggplot2 - – break –

- Interactive Session: Mapping with style

- – lunch –

- Interactive Session: Mapping with Google

- – break –

- Assignment: DIY maps

- – end –

Day 4 – The Enlightened Researcher

- Interactive Session: Tidy data

- – break –

- Interactive Session: Tidier data

- – lunch –

- Interactive Session: Tidiest data

- – end –

Day 5 – The world is yours

- Presentation: Recap

- – break –

- Interactive Session: Open Floor

- – lunch –

- Optional Session: More Open Floor

- – end –

1.2 About this Workshop

The aim of this five-day introductory workshop is to guide you through the basics of using R via RStudio for analysis of environmental and biological data. It is ideal for people new to R or who have limited experience. This workshop is not comprehensive, but is necessarily selective. We are not hardcore statisticians, but rather ecologists who have an interest in statistics, and use R frequently. Our emphasis is thus on the steps required to analyse and visualise data in R, rather than focusing on the statistical theory.

The workshop is laid out so it begins simply and slowly to impart the basics of using R. It then gathers pace, so that by the end we are doing intermediate level analyses. Day 1 is concerned with becoming familiar with getting data into R, doing some simple descriptive statistics, data manipulation and visualisation. Day 2 takes a more in depth look at manipulating and visualising data. Day 3 focuses on creating maps. Day 4 deals with the fundamentals of reproducible research. Day 5 allows one to utilise all of the skills learned throughout the week by creating a final project. The workshop is case-study driven, using data and examples primarily from our background in the marine sciences and real life situations. There is no homework but there are in class assignments.

Don’t worry if you feel overwhelmed and do not follow everything at any time during the Workshop; that is totally natural with learning a new and powerful program. Remember that you have the notes and material to go through the exercises later at your own pace; we will also be walking the room during sessions and breaks so that we can answer questions one on one. We hope that this Workshop gives you the confidence to start incorporating R into your daily workflow, and if you are already a user, we hope that it will expose you to some new ways of doing things.

Finally, bear in mind that we are self-taught when it comes to R. Our methods will work, but you will learn as you gain more experience with programming that there are many ways to get the right answer or to accomplish the same task.

1.3 Why use R?

As scientists, we are increasingly driven to analyse and manipulate datasets. As these datasets grow in size our analyses are becoming more sophisticated. There are many statistical packages on the market that one can use, but R is becoming the global standard. There are several reasons for this trend:

It is free, which is nice if you despise commercial software such as Microsoft Office, as we do — in fact, this entire document was written in Rmarkdown and the files supporting this Workshop material can be edited on any computer using a variety of operating systems such as Mac OS X, Linux and Microsoft Windows

It is powerful, flexible and robust; it is developed and used by leading academic statisticians

It contains advanced statistical routines not yet available in other software

The cutting-edge statistical routines open up scientific possibilities in creative new ways

It has state-of-the-art graphics

Users continually extend the functionality by updating existing packages and adding new ones and make these available for free

It does not depend on a pointy-and-clicky interface, such as SPSS, and requires one to write scripts — more on the advantages of scripts later

It is truly amazing that such a powerful and comprehensive package is freely available and we are indebted to the developers of R for going down this path.

1.3.1 Some negatives of using R

Although there are many positives of using R, there are some negatives:

It can have a steep learning curve for those whom do not like statistics or data manipulation, and it does require frequent use to remain familiar with it and to develop advanced skills

Error trapping can be confusing and frustrating

Rudimentary debugging, although there are some packages available to enhance the process

Handles large datasets (100 MB), but can have some trouble with massive datasets (GBs)

Some simple tasks can be tricky to do in R

There are multiple ways of doing the same thing

1.3.2 The challenge: learning to program in R

The big difference between R and many other statistical packages that you might have used is that it is not, and never will be, a menu-driven ‘point and click’ package. R requires you to write your own computer code to tell it exactly what you want to do. This means that there is a learning curve, but these are outweighed by numerous advantages:

To write new programs, you can modify your existing ones or those of others, saving you considerable time

You have a record of your statistical analyses and thus can re-run your previous analyses exactly at any time in the future, even if you can’t remember what you did — this is central to reproducible research

The recorded code can include the liberal use of internal documentation, which is often overlooked by practising scientists

It is more flexible in being able to manipulate data and graphics than menu-driven software

You will develop and improve your programming, which is a valuable general skill

You will improve your statistical knowledge

You can automate large problems

You can provide and share code that underpins published analyses; journals are starting to request the code for analyses in papers, to increase transparency and repeatability

Integration with tools like git (e.g. GitHub and Bitbucket) enable online collaboration in large statistical research programmes and they allow one to rely on version control systems

Programming is simply heaps more fun than point-and-click!

1.4 Using your own computer?

1.4.1 Installing R

It is straightforward installing R on your machine. Follow these steps:

Go to the CRAN (Comprehensive R Archive Network) R website. If you type ‘r’ into Google it is the first entry

Choose to download R for Linux, Mac or Windows

For Windows users, just install ‘base’ and this will link you to the download file

For Mac users, choose the version relevant to your Operating System

If you are a Linux user, you know what to do!

1.4.2 Installing RStudio

Although R can run in its own console or in a terminal window (Mac and Linux; the Windows command line is a bit limiting), we will use RStudio in this Workshop. RStudio is a free front-end to R for Windows, Mac or Linux (i.e., R is working in the background). It makes working with R easier, more productive, and organised, especially for new users. There are other front-ends, but RStudio is the most popular. To install:

Go to the RStudio website.

Choose the ‘Download RStudio’ button

Choose run ‘RStudio on your Desktop’ and follow the prompts

Choose the relevant ‘Installers for ALL Platforms’ to download

Install RStudio as per the instructions.

See you on Monday, 28 August 2017.

— Cheers, AJ and Robert

1.5 Resources

Below you can find the source code to some books and other links to websites about R. With some of the technical skills you’ll learn in this course you’ll be able to download the source code, compile the book on your own computer and arrive at the fully formatted (typeset) copy of the books that you can purchase for lots of money:

- ggplot2. Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis — the R graphics bible

- R for Data Science — data analysis using tidy principles

- R Markdown — reproducible reports in R

- bookdown: Authoring Books and Technical Documents with R Markdown — writing books in R

- Shiny — interactive website driven by R

1.6 Style and code conventions

Early on, develop the habit of unambiguous and consistent style and formatting when writing your code, or anything else for that matter. Pay attention to detail and be pedantic. This will benefit your scientific writing in general. Although many R commands rely on precisely formatted statements (code blocks), style can nevertheless to some extent have a personal flavour to it. The key is consistency. In this book we use certain conventions to improve readability. We use a consistent set of conventions to refer to code, and in particular to typed commands and package names.

- Package names are shown in a bold font over a grey box, e.g.

tidyr. - Functions are shown in normal font followed by parentheses and also over a grey box , e.g.

plot(), orsummary(). - Other R objects, such as data, function arguments or variable names are again in normal font over a grey box, but without parentheses, e.g.

xandapples. - Sometimes we might directly specify the package that contains the function by using two colons, e.g.

dplyr::filter(). - Commands entered onto the R command line (console) and the output that is returned will be shown in a code block, which is a light grey background with code font. The commands entered start at the beginning of a line and the output it produces is preceded by

R>, like so:

rnorm(n = 10, mean = 0, sd = 13)R> [1] -7.392528 1.493839 -0.930235 -5.216910 -23.652843 -5.398330

R> [7] 1.977597 16.606545 -4.948219 14.373923Consult these resources for more about R code style :

We can also insert maths expressions, like this \(f(k) = {n \choose k} p^{k} (1-p)^{n-k}\) or this: \[f(k) = {n \choose k} p^{k} (1-p)^{n-k}\]

1.7 About this document

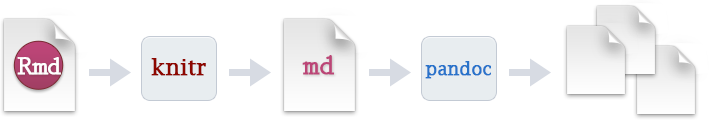

This document was written in bookdown and transformed into the ‘GitBook’ you see here by knitr, pandoc and (Figure 1.1). All the source code and associated data are available at AJ Smit’s GitHub page. You can download the source code and compile this document on your own computer. If you can compile the document yourself you are officially a geek – welcome to the club! Note that you will need to complete the exercises in the chapter, An R workflow, before this will be possible.

Figure 1.1: The Rmarkdown workflow.

You will notice that this repository uses GitHub, and you are advised to set up your own repository for R scripts and all your data. We will touch on GitHub and the principles of reproducible research later, and GitHub forms a core ingredient of such a workflow.

The R session information when compiling this book is shown below:

sessionInfo()R> R version 3.4.3 (2017-11-30)

R> Platform: x86_64-pc-linux-gnu (64-bit)

R> Running under: Ubuntu 16.04.3 LTS

R>

R> Matrix products: default

R> BLAS: /usr/lib/libblas/libblas.so.3.6.0

R> LAPACK: /usr/lib/lapack/liblapack.so.3.6.0

R>

R> locale:

R> [1] LC_CTYPE=en_ZA.UTF-8 LC_NUMERIC=C

R> [3] LC_TIME=en_ZA.UTF-8 LC_COLLATE=en_ZA.UTF-8

R> [5] LC_MONETARY=en_ZA.UTF-8 LC_MESSAGES=en_ZA.UTF-8

R> [7] LC_PAPER=en_ZA.UTF-8 LC_NAME=C

R> [9] LC_ADDRESS=C LC_TELEPHONE=C

R> [11] LC_MEASUREMENT=en_ZA.UTF-8 LC_IDENTIFICATION=C

R>

R> attached base packages:

R> [1] stats graphics grDevices utils datasets base

R>

R> loaded via a namespace (and not attached):

R> [1] compiler_3.4.3 backports_1.1.0 bookdown_0.5 magrittr_1.5

R> [5] rprojroot_1.2 tools_3.4.3 htmltools_0.3.6 yaml_2.1.14

R> [9] Rcpp_0.12.14 stringi_1.1.5 rmarkdown_1.6 highr_0.6

R> [13] knitr_1.17 methods_3.4.3 stringr_1.2.0 digest_0.6.15

R> [17] evaluate_0.10.11.8 Exercise: It which shall not be named

Now that you have heard (and perhaps read) our argument about the merits of using R, let’s double down and spend the next hour seeing first-hand why we think this. Please open the file ‘data/SACTN_data.csv’ in MS Excel. Gasp! Yes I know. After all of that and now we are using MS Excel? But trust us, there is method to this madness. Your mission, should you choose to accept it, is to spend the next hour creating monthly climatologies and plotting them as a line graph. The South African Coastal Temperature Network (SACTN, which will be used several times during this workshop) data are three monthly temperature time series, each about 30 years long. To complete this objective you will need to first split up the three different time series, and then figure out how to create a monthly climatology for each. A monthly climatology is the average temperature for a given month at a given place. So in this instance, because we have three time series, we will want 36 total values comprised of January - December monthly means for each site (if a time series is 30 years long, then a climatological December will be the mean temperature of all of the data within the 30 Decembers for which data are available). Once those values have been calculated, it should be a relatively easy task to plot them as a dot and line graph. Please keep an eye on the time, if you are not done within an hour please stop anyway. Less than a quarter of workshop attendees have completed this task in the past.

After an hour has passed we will take a break. When we return we will see how to complete this task via R as part of ‘The New Age’ demonstration.